Jacquard weaving loom. Biography of Joseph Marie Jacquard The incredible precision of the Jacquard machine

Joseph Marie Jacquard is a famous inventor of the 17th - 19th centuries. His main invention - an industrial method for producing fabric - is of great importance for modern computer science and helped develop the first prototype of electronic

Joseph Marie Jacquard: short biography

J. M. Jacquard (1754 - 1834) is famous for the invention of the industrial loom. The future French inventor was born in Lyon in 1752. As the son of a weaver, Joseph Jacquard was apprenticed to a bookbinder and was able to work in a foundry, an enterprise that created metal plates with type and ink for printing.

However, after the death of his father, his son inherited his business and became a weaver. Joseph lost his son during the French Revolution, then Lyon fell, the revolutionaries had to leave the city and go underground. Returning to his native Lyon, Jacquard took on any job and repaired many different looms in an attempt to take his mind off his grief.

In 1790, Joseph Marie Jacquard made the first attempt to create an industrial machine. Lyon at that time, as now, was a busy industrial area of France, with many trade routes passing through it from ports deeper into the continent. The inventor gets acquainted with autonomous machines Jacques de Vaucanson, who opened his own production in the city. Witty and elegant mechanical toys in the form of animals and people amazed Jaccard and helped correct the shortcomings of his own invention.

Recognition of Jacquard's merits by contemporaries

In 1808, work on the loom was completed. Having become an empire, France could no longer satisfy the needs of a huge, constantly warring army with the help of manual labor. The need for fabrics was urgent, so an industrial machine came in handy.

The achievements of Joseph Marie Jacquard were noted by Napoleon I, the weaver was entitled to a considerable pension from the state and was given the right to collect monetary contributions in his favor from each French loom of an invented design. In 1840, the noble residents of Lyon erected a monument in honor of the inventor who glorified the city.

Jacquard

Joseph's machines and the resulting fabric were called jacquard in honor of the creator. Jacquard had an unusually wide use both in past times and now. Outerwear, unusually beautiful dresses, as well as covers and upholstery for furniture are made from this fabric.

Fabric repeats contain at least 24 threads that weave unusually complex and beautiful patterns. Materials can be combined during creation, which makes it possible to create very interesting effects on finished products. Decorating home interiors in the Rococo and Baroque style is almost impossible without chic jacquard curtains, upholstery and pillows.

The complexity of making reports made the work of the craftsmen and the finished fabric incredibly expensive; only aristocrats and the rich could afford such a luxury. Dresses and outfits made of jacquard still amaze with the beauty of their patterns; for kings and close aristocrats, gold and silver threads were used in weaving.

The tight weave and intricate patterns create a unique relief and tapestry effect. The thicker the thread, the denser and stronger the fabric itself. Thin and soft jacquard is used for dresses, coarse and dense - for upholstery and covers, or even when creating carpets.

Jacquard weaving machine

The main difference of the machine invented by Jacquard was that the position of the thread in the pattern did not depend on its parity. Each thread in the pattern had its own weaving program. The position of the threads was controlled by simple cards made of thick paper - perforated prisms. Punch cards could control up to 100 threads and were of appropriate length.

The report prisms were stitched into one working tape and changed as needed by the machine operator. The machine itself is incredibly simple and yet effective. It necessarily includes a board-frame for the fabric and its cords, a large set of hooks and knives, needles and program pattern cards for each thread. All threads pass through the holes of the long board for even distribution. The hooks catch the spindle and can carry it beyond the reach of the blades. The warp threads are tensioned at the bottom of the device in a horizontal direction.

The needles move along slots in the program cards. They have cut and uncut areas; the operator can specify rocking and rotational movements of the prisms along which the control needles move. The uncut areas of the cards retract the needles and remove the hook from the spindle, while the active needle causes the hook to move the desired thread.

Elegant solution

The jacquard loom is an outstanding example of a computer-controlled machine, invented before the term "binary code" was coined. Punch cards change the position of the needle from “active” to “inactive” and embody the “zero/one” operating principle of all computer technology, known to all modern computer scientists.

Joseph's punch cards were used for their intended purpose much later, and his invention became the first programmable device and for a long time determined the direction of further development of industrial technology throughout the world.

What did the inventor not realize?

The invention of the industrial loom was a real breakthrough not only for contemporaries, but also brought closer the creation of autonomous computing technology by subsequent generations. Joseph Marie Jacquard apparently had no idea about the real significance of what he invented.

However, it was the simple cardboard weaving control tables that laid the principle for programming production lines in the future. Joseph Marie Jacquard can be called The practical achievements of the inventor are truly unique, because the theoretical foundations of the concept of an algorithm and the description of the simplest principles of programming were made only during the Second World War. The scientist developed his abstract machine to crack secret military ciphers, like the famous Enigma code.

Jacquard was born in 1752 into a weaver's family. From a young age, he had to wander around different regions of France and change a number of professions, including the profession of a type caster and bookbinder. In 1793-1794. we find Jacquard and his son in the ranks of the revolutionary army of the Convention, fighting the troops of monarchical Austria. The death of his son in one of the battles interrupted Jacquard's military service and forced him to return to Lyon. From that time on, until the end of his life, he devoted all his work to weaving.

Familiar since childhood with the plight of patterned weavers, Jacquard is well aware that the hour of the machine has come, that the future fate of the Lyon industry depends on it. At first, Jacquard sets himself only a modest task: to improve the Ponson-Verzier machine, making it more compact and reducing the number of pullers required to service it. The machine designed by Jacquard and patented by him in June 1800 was awarded a bronze medal, and its model was awarded a place in the Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (Descripsion des machines et procedes).

Despite the many ingenious improvements and additions made by Jacquard, this invention of his did not go beyond the beaten path and did not break with the old tradition. The design of the machine was very complex and the practical test did not live up to the hopes associated with the machine. But just two years later, Jacquard attracted everyone's attention with a brilliant solution to a problem presented simultaneously at competitions of the Society for the Encouragement of Crafts and Arts in France and the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Crafts and Arts in England - the invention of a stanchion for mechanical knitting of fishing nets. The result of this was an invitation from Jacquard to Paris, where he was to complete the construction of his new machine in the workshops of the Conservatory of Arts and Crafts.

Working in this experimental laboratory of French industrial technology, Jacquard becomes more familiar with the collection of machines from Vaucanson's office, located in the Conservatory, and finds in the attic ruins individual parts of a long-forgotten patterned machine of the brilliant French mechanic. Restoring the machine and testing it allows Jacquard to critically examine its positive and negative sides, to find its strengths and weaknesses. Jacquard decides to redesign the entire structure. He leaves for Lyon, where a group of manufacturers have already become interested in his find, offering the inventor financial assistance and setting up a special workshop for him to work on. Clever entrepreneurs enter into an agreement with Jacquard in advance on the assignment of all rights to a future invention to them in exchange for an annual pension of 3,000 francs (Ballot, Johannsen).

In 1804, a new machine, which was destined to make such a revolution in silk weaving as no other invention had ever achieved before or after it, was completed. Subsequently, this historical machine was installed in the Conservatory of Arts and Crafts, and from this preserved monument of technology one can judge the significance of Jacquard's invention (the patent for the machine in 1804 was not taken by the inventor).

This machine is shown in Fig. a and 6. Its central organ is a tetrahedral prism with drilled recesses, which supports a perforated tape placed on a moving carriage. The action of the pawl rotates the prism with each stroke (formation of the throat) by a quarter turn. Horizontally located needles with springs are located in a special needle box. A series of cards moves along an endless chain, allowing you to automatically create the desired fabric pattern. With each rotation of the prism, the card is pressed against its edge and directed towards the needles. Some needles pass freely through the hole of the card, others are moved to the side and remove their hooks from the knives, as a result of which the warp threads associated with the moved hooks do not rise and form the lower part of the pharynx. Freely passing needles leave hooks on the knives, which act on the hooks, and with the help of arcade cords and frame threads, they lift up those warp threads that need to be lifted to insert the shuttle. At this time, the prism moves away from the needle board, and the springs begin to push the shifted needles and hooks to their original position, which is necessary for the operation of the next cards. A new rotation of the prism and pressing of a new card onto the needle board produces another combination of selection of needles and warp threads. (More information about weaving with cards can be found here).

The total number of needles on the machine is equal to the number of holes on the four faces of the prism (Barlow, The History and principles of weaving).

|

This is how the Jaccard machine works. We see that in it the inventor successfully combined Falcon's principle of selecting threads with a perforated tape with Vaucanson's principle of pressing needles with a special apparatus moving on a carriage. To this Jacquard added significant new details: an endless chain for automatically moving the cards and a prism that combined the Falcon board and the Vaucanson cylinder, but now played the active role of a mechanism guiding the cards to the needle board. As a result, in the Jacquard machine the puller is completely eliminated from the production process, and the pattern can be sorted out outside the machine, which eliminates the downtime characteristic of previous machine systems and provides the ability to quickly change the pattern. The latter, thanks to the unlimited length of the cardboard chain, can be as complex as you like. Finally, the elementary nature of the operations that are reserved for the worker makes the high art of previous craftsmen completely unnecessary and allows the use of low-skilled weavers to operate the machine. In other words, Jacquard’s machine completely resolved the problems that were then facing French capitalist industry, and, using everything valuable that was available in previous designs, it turned a semi-mechanized apparatus into a real working machine.

“A critical history of technology,” says Marx, “would generally show how little of any invention of the eighteenth century belongs to any one individual.” The history of the Jacquard machine is one of the brilliant proofs of this.

Jacquard's machine, simple in design and manually driven, like the Jenny in England, did not initially cause a transition to the factory system, and from 1806 it began to be installed in many small enterprises in Lyon. According to a government decree of 1805, Jacquard received the right to deductions in his favor (in the amount of 50 francs) from each machine of his design used in the production. The practical distribution of the machine was delayed, however, in the early years by a number of design flaws of the machine. Here; First of all, they included the incredible noise produced by the movement of the carriage, discrepancies in the movement of the carriage and the prism, the unevenness of pressing the cardboard to the needles, and the high cost of the machine. The hand-printing of designs onto cardboard also showed that artisanal traits had not yet been completely overcome in the new machine. In its original form, Jacquard's loom, like Cartwright's simple mechanical loom, “represents only a more or less modified mechanical edition of the old craft tool” (Marx, Capital).

The first improvements in the Jacquard machine were made by the mechanic Bretgon, who, after several years of hard work, replaced the carriage with a press that precisely adjusted the travel of the prism, simplified the transmission mechanism of the machine, eliminating a number of blocks, counterweights and levers, which speeded up the work of the main organs of the machine, and introduced a method of production separately pattern and background of the fabric, due to which the number of empty cards was reduced by increasing the number of perforated cards, and thereby by increasing the repeat of the fabric. In the period 1815-1820. a number of French inventors give the machine that technically perfect appearance and practically cost-effective character, which remains almost unchanged for many decades.

The widespread use of the loom in France quickly lowered the wages of patterned weavers, which fell by 50% in 10-15 years. in 1825, over 10,000 jacquard looms were already operating in Lyon alone. In 1810, Jacquard's machine came to England and marked the beginning of factory silk weaving here. The machine began to be manufactured in English factories from metal parts and driven by a steam engine (Textile machinery. Catalog of Science Museum). Since 1816, the new machine has become famous in Austria and Prussia. In 1820, the Frenchman Dislin, who came to Moscow, sold one Jacquard machine for a large sum to the Russian government. The machine was installed in the house of a Moscow merchant for free viewing by the manufacturers. However, the lack of experienced craftsmen delayed the practical use of the new machine in Russia. Only in 1823, thanks to the work of master Kanengisser, the production of machine tools for private entrepreneurs was established. Within 5 years, Jacquard's machine became widespread in merchant and, partly, noble manufactories. In 1828, numerous silk-weaving enterprises in the Moscow province alone already had about 25,000 Jacquard looms (Journal of Manufactures and Trade, 1828).

Story

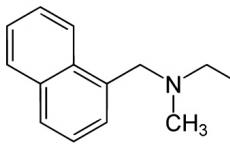

Named after the French weaver and inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard.

Application

When forming a shed on a weaving machine, a Jacquard machine makes it possible to separately control the movement of each thread or a small group of warp threads and produce fabrics whose repeat consists of a large number of threads. Using a jacquard machine, you can produce patterned dress and decorative fabrics, carpets, tablecloths, etc.

Description

The jacquard machine has knives, hooks, needles, frame board, frame cords and perforated prism. The warp threads, threaded into the eyes of the faces (healds), are connected to the machine using arcate cords threaded into a dividing board for uniform distribution across the width of the machine. The knives, fixed in the knife frame, perform a reciprocating movement in a vertical plane. The hooks located in the zone of action of the knives are captured by them and rise up, and through the frame and arcate cords the warp threads rise up, forming the upper part of the pharynx (the main overlaps in the fabric). The hooks, removed from the range of action of the knives, are lowered down along with the frame board. The lowering of the hooks and warp threads occurs under the influence of gravity of the weights. The lowered warp threads form the lower part of the shed (weft weaves in the fabric). The hooks are removed from the zone of action of the knives by needles, which are acted upon by a prism that has rocking and rotational movements. The prism is covered with cardboard consisting of separate paper cards, which have cut and uncut places opposite the ends of the needles. When meeting a cut place, the needle enters the prism, and the hook remains in the zone of action of the knife, and the uncut place on the card moves the needle and turns off the hook from interaction with the knife. The combination of cut and uncut places on the cards allows for a very definite alternation of raising and lowering of the warp threads and the formation of a pattern on the fabric.

A striking example of a program-controlled machine, created long before the advent of computers. The punch card is typed in binary code: there is a hole, there is no hole. Accordingly, some threads rose, some did not. The shuttle throws a thread into the formed shed, forming a double-sided ornament, where one side is a color or texture negative of the other. Since to create even a small pattern, about 100 or more weft threads and an even larger number of warp threads are required, a huge number of perforated cards were created, which were tied into a single ribbon. Scrolling, it could occupy two floors. One punched card corresponds to one shuttle throw.

- - knives;

- - frame board;

- - frame cords;

- - arcate cords;

- - dividing board;

- - faces;

- - weights;

- - needles;

- - perforated prism;

- - spring;

- - board;

- - hooks.

see also

Literature

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Links

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

See what "Jacquard loom" is in other dictionaries:

A machine used (usually in industry) for processing various materials, or a device for doing something. Wiktionary has an entry for "machine" ... Wikipedia

This article or section needs revision. Please improve the article in accordance with the rules for writing articles... Wikipedia

Contents 1 Paleolithic era 2 10th millennium BC. e. 3 9th millennium BC uh... Wikipedia

For many years, punched cards served as the main media for storing and processing information. In our minds, a punched card is firmly associated with a computer that takes up an entire room, and with a heroic Soviet scientist making a breakthrough in science. Punched cards are the ancestors of floppy disks, disks, hard drives, and flash memory. But they did not appear with the invention of the first computers, but much earlier, at the very beginning of the 19th century...

Falcon's machine Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his machine based on the first similar machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to come up with a system of cardboard punched cards connected in a chain.

Alexander Petrov

On April 12, 1805, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and his wife visited Lyon. The country's largest weaving center in the 16th-18th centuries suffered greatly from the Revolution and was in a deplorable state. Most of the manufactories went bankrupt, production stood still, and the international market was increasingly filled with English textiles. Wanting to support Lyon craftsmen, Napoleon placed a large order for cloth here in 1804, and a year later he arrived in the city in person. During the visit, the emperor visited the workshop of a certain Joseph Jacquard, an inventor, where the emperor was shown an amazing machine. The huge thing, installed on top of an ordinary loom, jingled with a long ribbon of perforated tin plates, and from the loom stretched, winding onto a shaft, silk fabric with the most exquisite pattern. At the same time, no master was required: the machine worked on its own, and, as they explained to the emperor, even an apprentice could easily service it.

1728. Falcon's machine. Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his machine based on the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to come up with a system of cardboard punched cards connected in a chain.

1728. Falcon's machine. Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his machine based on the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to come up with a system of cardboard punched cards connected in a chain.

Napoleon liked the car. A few days later, he ordered that Jacquard’s patent for a weaving machine be transferred to public use, and that the inventor himself be given an annual pension of 3,000 francs and the right to receive a small royalty of 50 francs from each loom in France on which his machine stood. However, in the end, this deduction added up to a significant amount - by 1812, 18,000 looms were equipped with the new device, and in 1825 - already 30,000.

The inventor lived the rest of his days in prosperity; he died in 1834, and six years later the grateful citizens of Lyon erected a monument to Jacquard on the very spot where his workshop had once been. The Jacquard (or, in the old transcription, "Jacquard") machine was an important building block of the Industrial Revolution, no less important than the railway or the steam boiler. But not everything in this story is simple and rosy. For example, the “grateful” Lyons, who subsequently honored Jacquard with a monument, broke his first unfinished machine and made several attempts on his life. And, to tell the truth, he didn’t invent the car at all.

1900. Weaving workshop. This photograph was taken more than a century ago in the factory floor of a weaving factory in Darvel (East Ayrshire, Scotland). Many weaving workshops look like this to this day - not because the factory owners spare money on modernization, but because the jacquard looms of those years still remain the most versatile and convenient.

1900. Weaving workshop. This photograph was taken more than a century ago in the factory floor of a weaving factory in Darvel (East Ayrshire, Scotland). Many weaving workshops look like this to this day - not because the factory owners spare money on modernization, but because the jacquard looms of those years still remain the most versatile and convenient.

How the machine worked

To understand the revolutionary novelty of the invention, it is necessary to have a general understanding of the operating principle of the weaving loom. If you look at the fabric, you can see that it consists of tightly intertwined longitudinal and transverse threads. During the manufacturing process, longitudinal threads (warp) are pulled along the machine; half of them are attached through one to the “shaft” frame, the other half - to another similar frame. These two frames move up and down relative to each other, spreading the warp threads, and a shuttle scurries back and forth into the resulting shed, pulling the transverse thread (weft). The result is a simple fabric with threads intertwined through one another. There can be more than two heald frames, and they can move in a complex sequence, raising or lowering the threads in groups, which creates a pattern on the surface of the fabric. But the number of frames is still small, rarely more than 32, so the pattern turns out to be simple, regularly repeating.

There are no frames at all on a jacquard loom. Each thread can move separately from the others with the help of a rod with a ring that catches it. Therefore, a pattern of any degree of complexity, even a painting, can be woven onto the canvas. The sequence of movement of the threads is set using a long looping strip of punched cards, each card corresponding to one pass of the shuttle. The card is pressed against the “reading” wire probes, some of them go into the holes and remain motionless, the rest are recessed with the card down. The probes are connected to rods that control the movement of the threads.

Even before Jacquard, they could weave complexly patterned canvases, but only the best masters could do it, and the work was hellish. A worker-puller climbed inside the machine and, at the command of the master, manually raised or lowered individual warp threads, the number of which sometimes amounted to hundreds. The process was very slow, required constant concentrated attention, and mistakes inevitably occurred. In addition, re-equipping the machine from one complex patterned canvas to another work sometimes took many days. Jacquard's machine did the work quickly, without errors - and by itself. The only difficult thing now was stuffing the punch cards. It took weeks to produce a single set, but once produced, the cards could be used again and again.

Predecessors

As already mentioned, the “smart machine” was not invented by Jacquard - he only modified the inventions of his predecessors. In 1725, a quarter of a century before the birth of Joseph Jacquard, the first such device was created by the Lyon weaver Basile Bouchon. Bouchon's machine was controlled by a perforated paper belt, where each passage of the shuttle corresponded to one row of holes. However, there were few holes, so the device changed the position of only a small number of individual threads.

The next inventor who tried to improve the loom was named Jean-Baptiste Falcon. He replaced the tape with small sheets of cardboard tied at the corners into a chain; on each sheet the holes were already located in several rows and could control a large number of threads. Falcon's machine turned out to be more successful than the previous one, and although it was not widely used, during his life the master managed to sell about 40 copies.

The third who undertook to bring the loom to fruition was the inventor Jacques de Vaucanson, who in 1741 was appointed inspector of silk weaving factories. Vaucanson worked on his machine for many years, but his invention was not a success: the device, which was too complex and expensive to manufacture, could still control a relatively small number of threads, and fabric with a simple pattern did not pay for the cost of the equipment.

1841. Carkill weaving workshop. The woven design (made in 1844) depicts a scene that occurred on August 24, 1841. Monsieur Carquille, the owner of the workshop, gives the Duke d'Aumalle a canvas with a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, woven in the same way in 1839. The fineness of the work is incredible: the details are finer than in engravings.

1841. Carkill weaving workshop. The woven design (made in 1844) depicts a scene that occurred on August 24, 1841. Monsieur Carquille, the owner of the workshop, gives the Duke d'Aumalle a canvas with a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, woven in the same way in 1839. The fineness of the work is incredible: the details are finer than in engravings.

Successes and failures of Joseph Jacquard

Joseph Marie Jacquard was born in 1752 in the outskirts of Lyon into a family of hereditary canutes - weavers who worked with silk. He was trained in all the intricacies of the craft, helped his father in the workshop and after the death of his parent inherited the business, but he did not take up weaving right away. Joseph managed to change many professions, was tried for debt, got married, and after the siege of Lyon he left as a soldier with the revolutionary army, taking his sixteen-year-old son with him. And only after his son died in one of the battles, Jacquard decided to return to the family business.

He returned to Lyon and opened a weaving workshop. However, the business was not very successful, and Jacquard became interested in invention. He decided to make a machine that would surpass the creations of Bouchon and Falcon, would be quite simple and cheap, and at the same time could produce silk fabric that was not inferior in quality to hand-woven fabric. At first, the designs that came out of his hands were not very successful. Jacquard's first machine, which worked properly, made not silk, but... fishing nets. He read in the newspaper that the English Royal Society for the Promotion of the Arts had announced a competition for the manufacture of such a device. He never received an award from the British, but his brainchild became interested in France and was even invited to an industrial exhibition in Paris. It was a landmark trip. Firstly, they paid attention to Jacquard, he acquired the necessary connections and even got money for further research, and secondly, he visited the Museum of Arts and Crafts, where Jacques de Vaucanson’s loom stood. Jacquard saw him, and the missing parts fell into place in his imagination: he understood how his machine should work.

With his developments, Jacquard attracted the attention of not only Parisian academics. Lyon weavers quickly realized the threat posed by the new invention. In Lyon, whose population at the beginning of the 19th century was barely 100,000, more than 30,000 people worked in the weaving industry - that is, every third resident of the city was, if not a master, then a worker or apprentice in a weaving workshop. Trying to simplify the fabric making process would put many people out of work.

Incredible precision of the Jacquard machine

The famous painting “The Visit of the Duke d'Aumale to the Weaving Workshop of Monsieur Carquille” is not at all an engraving, as it might seem, the design is completely woven on a loom equipped with a jacquard machine. The size of the canvas is 109 x 87 cm, the work was carried out, in fact, by the master Michel-Marie Carquilla for the company Didier, Petit and Si. The process of mis en carte - or programming an image on punched cards - lasted many months, with several people doing it, and the production of the canvas itself took 8 hours. The tape of 24,000 (over 1000 binary cells each) punched cards was a mile long. The painting was reproduced only on special orders; several paintings of this type are known to be stored in different museums around the world. And one portrait of Jaccard woven in this way was commissioned by the Dean of the Department of Mathematics at Cambridge University, Charles Babbage. By the way, the Duke d’Aumale, depicted on the canvas, is none other than the youngest son of the last king of France, Louis Philippe I.

As a result, one fine morning a crowd came to Jacquard’s workshop and broke everything he had built. The inventor himself was strictly punished to leave his evil ways and take up a craft, following the example of his late father. Despite the admonitions of his brothers in the workshop, Jacquard did not abandon his research, but now he had to work secretly, and he completed the next car only by 1804. Jacquard received a patent and even a medal, but he was wary of selling “smart” machines on his own and, on the advice of merchant Gabriel Detille, he humbly asked the emperor to transfer the invention to the public property of the city of Lyon. The emperor granted the request and rewarded the inventor. You know the end of the story.

Punch card era

The very principle of the jacquard machine - the ability to change the sequence of operation of the machine by loading new cards into it - was revolutionary. Now we call it “programming”. The sequence of actions for the jacquard machine was specified by a binary sequence: there is a hole - there is no hole.

1824. Difference machine. Babbage Charles Babbage's first attempt at building an analytical engine was unsuccessful. The bulky mechanical device, which was a collection of shafts and gears, calculated quite accurately, but required too complex maintenance and highly qualified operator.

1824. Difference machine. Babbage Charles Babbage's first attempt at building an analytical engine was unsuccessful. The bulky mechanical device, which was a collection of shafts and gears, calculated quite accurately, but required too complex maintenance and highly qualified operator.

Soon after the jacquard machine became widespread, perforated cards (as well as perforated tapes and disks) began to be used in a variety of applications.

Shuttle machine

At the beginning of the 19th century, the main type of automatic weaving device was the shuttle loom. It was designed quite simply: the warp threads were pulled vertically, and a bullet-shaped shuttle flew back and forth between them, pulling a transverse (weft) thread through the warp. From time immemorial, the shuttle was pulled by hand; in the 18th century this process was automated; the shuttle was “shot” from one side, received by the other, turned around - and the process was repeated. The shed (the distance between the warp threads) for the passage of the shuttle was provided with the help of a reed - a weaving comb, which separated one part of the warp threads from the other and lifted it.

But perhaps the most famous of these inventions - and the most significant on the path from the loom to the computer - is Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine. In 1834, Babbage, a mathematician inspired by Jaccard's experience with punched cards, began work on an automatic device for performing a wide range of mathematical problems. He had previously had the unfortunate experience of building a “difference engine,” a bulky 14-ton monster filled with gears; The principle of processing digital data using gears has been used since the time of Pascal, and now they were to be replaced by punched cards.

1890. Hollerith's Tabulator. Herman Hollerith's tabulating machine was built to process the results of the 1890 American Census. But it turned out that the machine’s capabilities went far beyond the scope of the task.

1890. Hollerith's Tabulator. Herman Hollerith's tabulating machine was built to process the results of the 1890 American Census. But it turned out that the machine’s capabilities went far beyond the scope of the task.

The analytical engine contained everything that is in a modern computer: a processor for performing mathematical operations (“mill”), memory (“warehouse”), where the values of variables and intermediate results of operations were stored, there was a central control device that also performed input functions. output. The analytical engine had to use two types of punched cards: large format, for storing numbers, and smaller ones - program ones. Babbage worked on his invention for 17 years, but was never able to finish it - there was not enough money. The working model of Babbage's Analytical Engine was built only in 1906, so the immediate predecessor of computers was not it, but devices called tabulators.

A tabulator is a machine for processing large volumes of statistical information, text and digital; information was entered into the tabulator using a huge number of punched cards. The first tabulators were designed and created for the needs of the American census office, but they were soon used to solve a variety of problems. From the very beginning, one of the leaders in this field was the company of Herman Hollerith, the man who invented and manufactured the first electronic tabulating machine in 1890. In 1924, Hollerith's company was renamed IBM.

When the first computers replaced tabulators, the principle of control using punched cards was retained here. It was much more convenient to load data and programs into the machine using cards than by switching numerous toggle switches. In some places, punch cards are still used today. Thus, for almost 200 years, the main language in which people communicated with “smart” machines remained the language of punched cards.

The article “The Loom, the Great-Grandfather of Computers” was published in the magazine Popular Mechanics (

At the beginning of the 19th century, French weaver and inventor Joseph-Marie Jacquard invented a new technology for industrially applying patterns to fabric. Nowadays such fabrics are called jacquard, and his machine is called a jacquard loom. Jacquard's invention makes it possible to obtain various light effects on the surface of the fabric, and in combination with different colors and thread materials - beautiful, soft transitions of tones and sharply defined contours of patterns, sometimes very complex (ornaments, landscapes, portraits, etc.). Jacquard is used for sewing dresses, outerwear, furniture fabrics, curtains, as well as for making lanyards, badge ribbons and other promotional materials (stripes, chevrons, labels, promotional tapes).

Joseph Jacquard was born on July 7, 1752. in Lyon. His father owned a small family weaving business (two looms) and Joseph also began his working career as a child in one of the many weaving factories in Lyon. But this hard and unsafe work did not attract him, and the future inventor went to study and work in a bookbinding shop.

But Jacquard was not destined to become an outstanding inventor in bookbinding or book printing. Soon his parents die, and he inherits looms and a small plot of land. As a result of several unsuccessful business projects, Joseph loses most of his father's inheritance, but at the same time becomes interested in the engineering problem of improving the weaving loom.

Despite the rapid development of weaving production in France, the capabilities of the  looms were very limited. Single-color fabrics or colored stripes were produced en masse. Fabrics with embroidered patterns were still made by hand. Jacquard wanted to improve the loom so that patterned fabrics could be produced industrially.

looms were very limited. Single-color fabrics or colored stripes were produced en masse. Fabrics with embroidered patterns were still made by hand. Jacquard wanted to improve the loom so that patterned fabrics could be produced industrially.

By 1790, Jacquard had created a prototype of the machine, but his active participation in revolutionary events in France did not allow him to continue working on improving his invention. After the revolution, Jacquard continued his design quest in a different direction. He invented a machine for weaving nets and in 1801 he took it to an exhibition in Paris. There he saw the loom of Jacques de Vaucanson, which as early as 1745 used a perforated roll of paper to control the weave of threads. What he saw gave Jacquard a brilliant idea, which he successfully used in his loom.

To control each thread individually, Jacquard came up with a punched card and an ingenious mechanism for reading information from it. This made it possible to weave fabrics with patterns predetermined on a punched card. In 1804, Jacquard's invention received a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition, and he was issued a corresponding patent. The final industrial version of the jacquard loom was ready by 1807.

In 1808, Napoleon I awarded Jacquard a prize of 3,000 francs and the right to a bonus of 50 francs per person.  a machine of his design operating in France. By 1812, more than ten thousand jacquard looms were in operation in France. In 1819, Jacquard received the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

a machine of his design operating in France. By 1812, more than ten thousand jacquard looms were in operation in France. In 1819, Jacquard received the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Joseph Marie Jacquard died in 1834 at the age of 82. In Lyon in 1840 a monument was erected to him. The Jacquard loom made it possible not only to industrially weave fabrics with complex patterns (Jacquard), but also became the prototype of modern automatic looms.

The Jacquard machine is the first machine that used a punched card in its work.

Already in 1823, the English scientist Charles Babaj tried to build a computer using punched cards. At the end of the 19th century, an American scientist built a computer and processed the results of the 1890 population census on it. Punched cards were used in computing until the mid-twentieth century.